Florida: 1961

The state of Florida has always been famous for our tourism, our oranges, and most recently, the hilarious antics of “The Florida Man”. But while Florida will always hold a special place in America’s heart for its ridiculousness, it also holds a special place in the United States of America’s Judicial System. In 1963, a Florida man named Clarence Earl Gideon was charged with Felony Breaking and Entering. Not having the money to hire an attorney, Gideon asked the state court to appoint him one. However, at that time, Florida state law could only appoint an attorney to an indigent (poor) defendant if they were charged with a capital offense- think murder, or something of the sort. In lieu of an attorney and with no money to hire one, Gideon- a man with no legal experience whatsoever- was forced to represent himself in trial. Gideon was found guilty by a jury of his peers and sentenced to five years in state prison.1

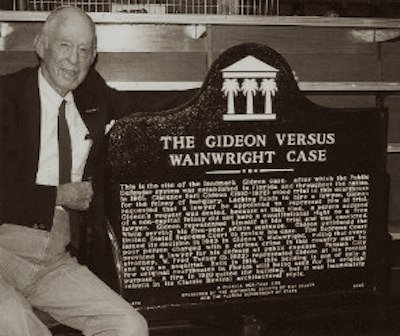

Having felt misrepresented and having his rights violated, Gideon then filed a petition- a habeus corpus– against Louie L. Wainwright, the Director of the Florida Division of Corrections, in the Florida Supreme Court and argued that his 65th Amendment Right to be represented by legal counsel in a trial was violated. When the Florida Supreme Court denied his appeal, Gideon v. Wainright climbed its way up the legal ladder and ended up in the white halls of the Supreme Court of the United States. In an unexpected and historic unanimous vote, the Supreme Court ruled that according to the Constitution, state courts must also appoint attorneys for indigent defendants- those who cannot afford to hire attorneys on their own.2 This decision opened the gateway for a brand new wave of indigent defense across the country.

But some things we as Americans must ask ourselves are:

- Why has indigent defense, throughout history, been so… ineffective?

- Does government-issued counsel actually end up helping or hurting our indigent citizens?

Both in modern and historic times, prosecutors have always had the upper-hand over public defenders in regards to money, resources, and staffing. Sometimes, public defenders do not even meet their clients until days, hours, or minutes before a trial. But why? What is the reason for such a large gap between indigent defense and it’s goal of effectiveness? How can we as a society enlighten our understanding of the American judicial process in order to make sense of such a discrepancy? In what ways can we change the way our legal system works so that all citizens have access to legal counsel that is on par with the State’s prosecution in both skill and resources?

The rhetoric in these rhetorical questions pose a moral and ethical dilemma in regards to how the law views us and our indigent peers. At the end of the day, we must realize that this problem comes down to an issue of morality, ethics, and most importantly, history. The hot question for the American judicial system is: What are we doing wrong, and how can we fix it?